It all started in a bedroom in a Colorado mountain town, when a 14-year-old boy grabbed the materials around him — fishing twine, legos, and the motors of toy airplanes — to create his first robotic arm.

Over time, this young teen made resourceful improvements to these limbs: dental rubber bands from braces moved the fingers, a windshield wiper motor from a car became an elbow motor. Soon, this hacked together robotic hand could shake hands, toss a ball, even interact with people.

Through tireless trial and error, 3D printing and teenage resourcefulness, this robotic hand would evolve into one of the most efficient, affordable prosthetic arms on the market. In just a few years, the young inventor would meet President Obama and work at Microsoft and NASA, using his mastery of robotics to introduce a new kind of prosthetic limb.

Easton LaChappelle, now 22 years old, is not only changing the prosthetic industry through these low cost, customizable human-like limbs, but is also changing the lives of amputees. Today, his company, Unlimited Tomorrow, has raised $1,109,291 and counting through our equity crowdfunding platform.

LaChappelle partially credits his small hometown of Mancos, Colorado. With a population of around 1,300 and a graduating class of 23 students, he became curious about the world outside of Mancos early on.

“That actually motivated me to go outside of the education system and learn on my own, and start turning my ideas into reality,” LaChappelle says. “I was a kid who took apart everything from microwaves to every toy and appliance I could get my hands on.”

He ripped open gadgets and stared with wonder at the small black chips inside of them — integrated circuits — and did everything he could to learn more. So he used the internet as his afterschool classroom.

“That started just accelerating my learning like crazy,” LaChappelle says. “I could talk to people through Skype across the world. They didn’t know I was 14 at that time.”

The open source community provided the designs and raw information for LaChappelle to build his first robot. And the cash-strapped boy was resourceful: He used fishing line for the tendons, motors from RC airplanes to move it, Legos as supports and electrical tape to piece it all together.

“I had no idea about amputees or prosthetics, this was just a cool project,” he remembers. “The greatest thing for it all was when I saw it work for the first time. That was such an amazing feeling. It’s like practicing for a test and getting a perfect score on it.”

LaChappelle was hooked. He couldn’t stop thinking of all the ways he could improve on his design.

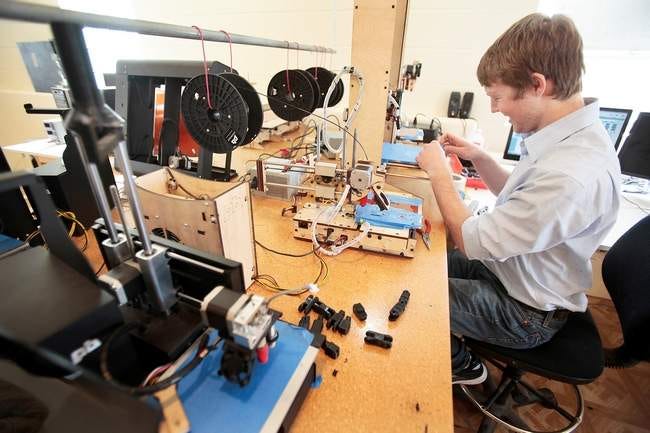

At the same time, 3D printers were first lasering their way onto the consumer market. LaChappelle was eagerly watching them on crowdfunding sites, and that’s where he bought his first one. He picked up a wooden 3D printer that he assembled himself and started learning how to “think in 3D.”

Around this time, LaChappelle was paying it forward to the online communities that had taught him so much by sharing his own work on YouTube. He started getting media attention, and that’s when his first big break happened: Popular Mechanics reached out to him.

“They sent a big film crew over to my bedroom pretty much, when I was 15 years old, and did this big photo shoot,” LaChappelle says.

Things were heating up. He entered his full prosthetic arm into the International Science Fair and came in second place. Then, the White House called.

“I brought my robotic arm into the White House,” LaChappelle says, “I shook hands with President Obama, I got to talk with him for about five minutes, and he loved it.”

Then, NASA read the Popular Mechanics story and contacted the teen.

“I received a call from the Johnson Space Center in Houston saying, ‘Hey, this is NASA. We’re wondering what you’re doing over the summer,’” he remembers. “Pretty much when NASA calls you asking that, you’re not doing anything over the summer.”

At the ripe age of 17, he worked on the Robonaut team, essentially working to replace human astronauts with robots on spacewalks. The goal? Sending a robot to the International Space Station. LaChappelle trained robots to do human-like tasks through gloves or VR headsets. The machines echoed his movements.

“It was a huge learning experience — I saw a lot of the inefficiencies of the government and budgets and everything like that,” he says. “It really validated what I was doing more because I can move a lot faster, and I could be a lot more nimble and use broader technology.”

So LaChappelle committed himself to private enterprise. Around this time, he met a small girl at a science fair who was wearing a $80,000 prosthetic arm. It made him realize just how unaffordable prosthetics were on the market at the time — and that he had the skills to do something about it.

“That changed my whole thought process,” he remembers. “This is not just making something cool in my bedroom anymore, this can actually really help people. I saw it really firsthand, no pun intended, but … Actually, yes, pun intended — and it really shocked me.”

Most prosthetics are heavy, difficult to use and can cost up to $100,000 — an amount not everyone can afford. Through low-cost scanners and 3D printers, this young scientists was able to make a prosthetic arm customized for each amputee that weighs and costs significantly less than its predecessors.

He realized that existing prosthetics weren’t just expensive. They were also heavy, especially for small children, and they lacked customization, so they didn’t match their owners’ skin colors or daily needs.

“I saw a lot of personal struggle,” he says. “That’s what really motivated me to actually turn this into something more.”

The age of 17 was the busiest of his life to date, LaChappelle says. He spoke at universities around the world, and in between that, he managed to get even better at 3D modeling to make his devices incredibly lightweight. He also wanted amputees to more naturally control their prosthetic hands through muscle movements, so he studied brainwave technologies.

“I had three 3D printers in my bedroom running 24/7 pretty much, just making new designs,” he says.

Not too long afterward, LaChappelle gave a pivotal TED Talk about his life story. As a result of that speech, Tony Robbins asked him to go into business together. Robbins provided things that were key to the budding business: startup capital, mentorship, contacts.

As a result, LaChappelle’s company Unlimited Tomorrow was founded in February of 2014.

Another pivotal contact came along when Microsoft approached the young engineer to ask how they could help his important mission. Up till then, he had been “pretty much hacking an Xbox Kinect to scan people,” he says. LaChappelle worked at the Seattle headquarters and learned about artificial intelligence and how he might integrate it to make his arms even better.

“They introduced me and my story to their secret R&D team that works on the next generation of products, and they loved what I was doing, they wanted to help,” he says. “They originally agreed to have me come in for about three weeks, I ended up staying there for about three months. Everybody who saw this project fell in love with it.”

“She’s like the perfect first person to receive this because if she doesn’t like it, she will tell you straight up,” he says. “She doesn’t really have a bias, which was amazing ’cause we want that honest feedback.”

Through Momo, LaChappelle wanted to validate the model: creating prosthetics that could be unique to each individual and fit them like a glove. But it wasn’t just a moment for research — it was also emotional.

“The first time I met Momo in person was to actually give her the final device,” he remembers, “which was just this amazing moment that everything was building up to.”

All of those years of studying, mowing lawns to earn materials, and trial and error paid off when Momo loved her new hand.

Thanks to the power of Unlimited Tomorrow’s story and its potential to change lives, donors kept appearing and asking to contribute. LaChappelle created a GoFundMe just to keep up with the outpouring of generosity. But the company wanted to take it to the next level.

“This is a people business and we wanted to have people help and contribute, and everybody wants to do that,” he says. “So, it was a pretty obvious, logical next step for us and it’s this really exciting kind of new part of raising money, and so far it’s been really amazing.”

LaChappelle decided to open up the company to investors through Indiegogoso that more people could add to the story of Unlimited Tomorrow. He felt like he was giving them an opportunity to be a part of something positive. Not only that, but ordinary people were the ones who had helped Unlimited Tomorrow to become truly unlimited.

“I feel it’s a small way to have them be involved in the big picture and help really change an industry, to help people around the world. So far, we’ve hit it right on the dot, where people want to be a part of something bigger. “

And indeed, investors have followed him: The Indiegogo campaign page has raised $1,109,291 to date. Thanks to their support, the company is almost finished with its first product development. It’s aiming to launch with sales in August.

“That will allow us to grow our commercial space, hire the core team that we really need to be able to turn this business into a company that can really compete within this industry,” he says.

Unlimited Tomorrow will be launching another IndieGoGo campaign later in the year to create, test and donate 100 devices. Now, each costs as little as $5,000, but they’re hoping to raise $1,000,000 to give away those first 100 units for free.

“So, we have it on one little girl named Momo — the next step is 100 and thousands and tens of thousands, millions.”

By giving away the product, the team hopes to work with the amputees closely, refine their model and begin making a noticeable change in the industry from the first day. Unlimited Tomorrow is also working with companies and organizations around the world to get amputees this technology at a global level.

The team plans on mastering upper body prosthetics, and then they’ll move into legs and feet. They’re even looking at devices that assist with exoskeletons, which can help patients with MS or who’ve suffered from a stroke to regain mobility and improve their daily lives.

The real goal? “To augment the human body.”

But first, crowdfunding.

“Our goal is to get this to as many people around the world as possible,” LaChappelle says. “That takes money, so we’re gonna find that money to be able to make that happen.”